OTAs help all ages regain health and well-being

In December 2019, Gaye Catlin was standing on a stepladder in her garage, reaching for holiday decorations, when she lost her balance and fell. Unable to move, she was incapacitated for approximately an hour until found by her husband.

Fast forward to April 2023, when Gaye visited the classroom of LLCC’s occupational therapy assistant (OTA) program to speak of her long, intensive road to recovery, including many months spend in a skilled rehabilitation facility. Gaye told students how important their work is in helping patients with traumatic and life-changing injuries, even though patients “may not like you at the time.” She encouraged them to be persistent yet understanding as they work with patients on various therapy strategies. She said they would be appreciated later when patients realized how they had helped them regain their strength and mobility.

OTAs help individuals regain the day-to-day skills lost to a stroke, aging or accidents. Skilled care facilities are the number one employer of OTAs.

K-12 schools are the second most frequent employers of OTAs, where they assist students to enhance motor, social and coping skills.

Upskilling for a new career

The need for OTAs is predicted to grow by 31% in the next five years, according to Dr. Yvonne Cosentino, director of LLCC’s OTA program. “Baby Boomers are aging. They are more active and take more risks than previous generations, leading to more fractures and injuries. Rehabilitation centers are full, and the need is always there in skilled nursing centers and hospitals. Also, OTAs are needed in schools to work in federally mandated programs for children with delays.”

She said Illinois is one of the top states for OTA salaries. “The average national salary for an OTA is $64,000, and our graduates usually start at $50,000-$60,000.”

Peter Shih has an arts degree and is a licensed massage therapist looking to upskill. He joined LLCC’s OTA program last year and qualified for the Pathways for the Healthcare Workforce (PATH) program, which pays for his tuition, books and fees while providing a stipend.

“OTA is a very dynamic field, working with clients, getting to know their stories and helping them regain function in their daily lives,” says Shih.

At the Healthy Minds, Hearts and Hands afterschool program (see box at right), Shih created activities that helped the young students focus. “For instance, we’d start with a yoga exercise, then I asked them, ‘What did you get for Christmas?’ I asked them to draw it out for me. It was great to see them all focus and how they improved together.”

After graduation, Shih would like to work with school children with special needs. “That’s my calling. Kids with behavior disorders or autism benefit from occupational therapy. Their interpretation of senses is disrupted. Occupational therapy can help them focus and in how they interact with the environment.”

What makes a great OTA?

“You have to be passionate about helping people achieve their individual goals when working with a person who’s been injured,” says Dr. Cosentino. “You let them know they can improve, help them see what their strengths are and guide them into developing goals for improvement and independence. You have to persevere, become the coach and modify plans to adapt to an individual’s needs.”

Healthy Minds, Hearts and Hands project

“Public school students lost three semesters of in-person learning due to the pandemic,” says Dr. Cosentino. “We had the idea of bringing our OTA students into a school with underserved students who could benefit from what we offer.”

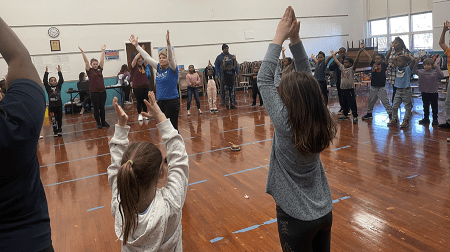

LLCC’s OTA program partnered with the Boys & Girls Clubs of Central Illinois for the service-learning project Healthy Minds, Hearts and Hands. The project at DuBois Elementary School included engaging activities to promote fitness, emotional well-being and social language development and was funded by an LLCC Innovation in Diversity and Inclusion grant.

OTA students worked with 2nd-5th graders. “We found that the children were having challenges with multi-step directions after so much computer work at home where you just ‘click.’ Our students brought games that focused on motor skills and helped them with academic needs.

“In every area, the children improved during the eight-week program, especially in social interactions and executive function. We plan to go into the schools again this fall as a level-one fieldwork site, and with parental permission, work individually with students who need more help.”